The Giant Panda’s large paws create deep vibrations on the soft dirt as it rustles through the emerald greens of the forest, bamboo at lip.

by Jackie Korcz

- In 2016, the Giant panda was downgraded from Endangered to Vulnerable on the IUCN Red-List.

- A combination of behavioural research, environment protection and captive breeding assists conservation programmes.

- WWF is working in China, and Conjour interviewed Regional Officer Nicola Loweth to find out what’s being done.

About the Giant Panda

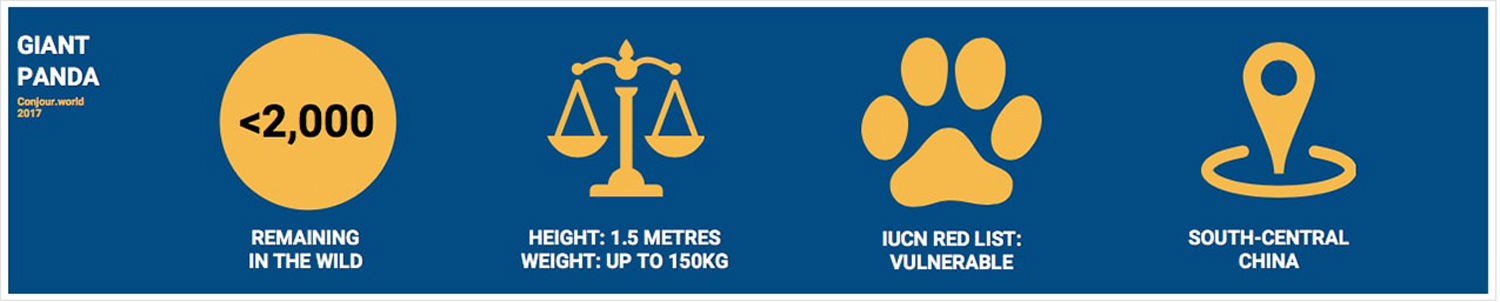

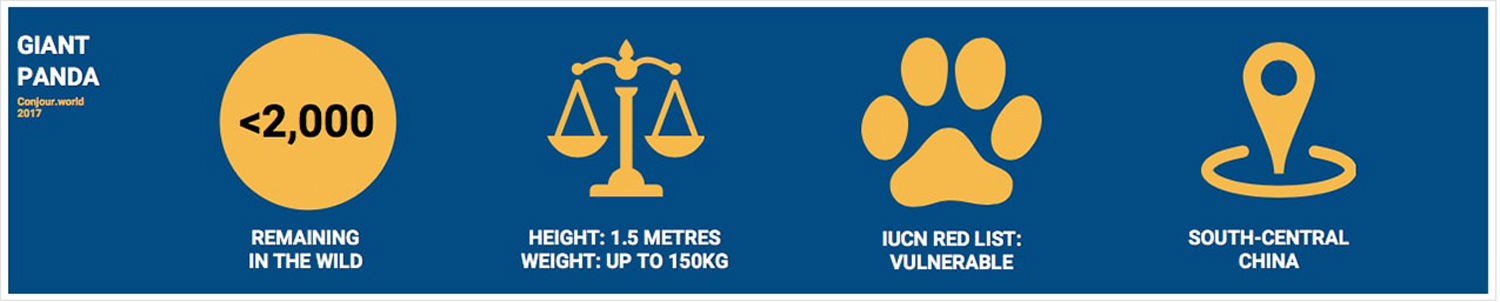

The giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca), although belonging to the order Carnivora, has in fact a diet consisting of 99% bamboo plant, and its distinctive black and white – and thick – coat is an adaptation to their climatic zone. Once reaching a fully matured age, a giant panda can stand at 1.5 metres tall with a bearing weight of 150kg. Males are much bigger than females, estimated to be around 10% larger and 20% heavier on average.

There are two incredibly unique features to the giant panda. It has noticeably broader, flat molar teeth which enable them to crush the bamboo to digest it as food. The wrist bones are also enlarged, which function as an opposable thumb, allowing the panda to grab bamboo at awkward angles, and hold it for longer periods of time due to their slow and continuous eating habits.

The sexual maturity of the giant panda peaks at around five and a half years. The females are not monogamous, and will breed with several males throughout their lifetime. Males and females tend to steer clear of one another unless breeding or competing, in which case they will only be in contact from around two to four days before returning to their isolated lifestyles. A female’s gestation period can vary quite dramatically, between 95-160 days, and they will usually only rear a single cub.

The panda cubs are born incredibly small in comparison to their adult size, reaching only 130g at birth, and will be dependent on its mother for the first few months of its life. By the age of eight or nine months they are normally fully weaned off their mother.

Despite its preference for solidarity, the giant panda does communicate with its counterparts through vocalisation and scent. By marking its territory through spraying, clawing trees and rubbing objects, a giant panda provides neighbouring individuals an understanding of its boundaries via scent (WWF Global 2016).

Finding Giant Panda Trends

Understanding trends that a species holds – such as when they breed, when they migrate or, on a more minute level, when they are most active – plays an important role in conservation biology. Animal behaviour allows us to understand how best to care for both the animals and the environment they inhabit. Studies have previously found trends in the giant panda’s daily and seasonal routines.

For the giant panda, studies have previously found trends in daily and seasonal activity routines. Using GPS collars, the impact of day, season and weather was studied, finding that activity peaked in pandas in early morning, afternoon and midnight. There was also a peak in June, followed by a large decrease in activity during August and September. This same study discovered, in particular, that the giant panda would be most active during periods of which solar radiation was highest, especially during the coolest seasons. On top of this, the study explored the idea of the energy budget, which represents how an animal divides its time into different activities. Giant pandas must put a lot of consideration into this, due to their low-nutrient diet. This means they must adjust their time budgets by modifying their periods of peak activity (Zhang, Hull & Huang 2015).

Once spread throughout most of China, northern Vietnam and northern Myanmar, the giant panda is now restricted to six isolated mountain ranges in south-central China, as well as in captivation as part of breeding programs around the world.

Giant Panda Conservation

Although very recently being removed as an endangered species on the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature) red-list for endangered species, the giant panda is still listed as Vulnerable (IUCN 2016). This downgrade may have had the negative effect of lulling the public into thinking the panda is out of hot water.

The species’ numbers may be increasing per each wild population, however, the threats to the giant panda are consistent and in some cases form part of a growing industry. Nicola Loweth, regional Officer of the India-China Unit in WWF’s Giant Panda Programme in China, says that “expanding human population and development has been the biggest drive for the restricted range of the giant panda’s habitat.”

Loweth explained that during the 1970s and 1980s, when expansion of industries suddenly increased, deforestation, habitat destruction and poaching were the largest killers of the species.

“The panda’s range was reduced by timber harvesting and forest clearance for arable land use to cultivate crops. Community activities such as livestock grazing, over-collection of wild plants and non-timber forest products, wood collection for heating, cooking and house construction also contributed to habitat degradation whilst poaching killed as many as 400 pandas.”

Captive Breeding the Giant Panda

Due to the extensive loss of habitat for the species, captive breeding programmes were started in certain zoos to encourage the species to increase its numbers. Loweth said that, until the 1990s, the species’ captive-breeding programmes faced several obstacles:

“Low oestrus rates, low conception rates and high neonatal mortality.”

However, these obstacles have since been overcome due to extensive scientific research on the breeding patterns and mannerisms of the animal.

Loweth continued to explain that due to the success in recent captive-breeding programmes, as well as the re-introduction of the species in the wild and the establishment of protected areas in which the giant pandas habituate, the species has successfully overcome its classification of endangerment, and been re-classified as Vulnerable.

“The banning of logging natural forests, providing subsidies to return farmland to forest, increasing penalties to poaching and designating a number of new nature reserves” have all been positive changes in improving the species’ situation, she said.

This does not mean, of course, that the giant panda is no longer at risk of extinction. As Loweth elaborated on, the population of giant pandas is “highly fragmented, split into 33 smaller groups, 18 of which have less than ten individuals.”

Additionally, it has been found that certain populations are not genetically viable in the longer term and thus are at risk of local extinction.

With all the above in mind, the giant panda must still have programmes and plans in place for the species to survive in the wild. You can help the species thrive in the future by spreading awareness, donating to WWF who create various conservation programmes, and prevent the species’ forests from being destructed by avoiding products containing ingredients like palm oil.

Captions and credits for images, from top-down:

– Feature Image – Giant Panda: Jcwf from nl [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

– Baby Giant Panda: By Sepht (Own work) [GFDL, CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

– Panda Enclosure: By Aaron Logan [CC BY 1.0], via Wikimedia Commons

References

Zhang, J., Hull, V., Huang, J., Zhou, S., Xu, W., Yang, H., McConnell, W.J., Li, R., Liu, D., Huang, Y. and Ouyang, Z., 2015. Activity patterns of the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca). Journal of Mammalogy, p.gyv118.

World Wildlife Fund (2016). What do pandas eat? Available at: http://wwf.panda.org/what_we_do/endangered_species/giant_panda/panda/what_do_pandas_they_eat/ (Accessed: 01 December 2016).

World Wildlife Fund (2016). Life cycle of Pandas. Available at: http://wwf.panda.org/what_we_do/endangered_species/giant_panda/panda/panda_life_cycle/ (Accessed: 02 December 2016).

IUCN (2000) Ailuropoda melanoleuca (Giant panda). Available at: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/712/0 (Accessed: 28 November 2016).

You must be logged in to post a comment Login