Wildlife Photography

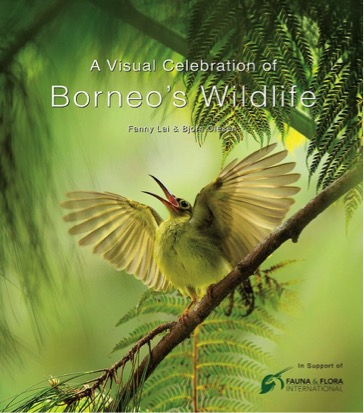

A Visual Celebration of Borneo’s Wildlife

In the recent past, Borneo has become more famous for its high rates of deforestation, forest fires and haze problems. Fanny Lai and Bjorn Olesen, along with editor Yong Ding Li, have compiled one of the most comprehensive photographic tributes to the natural wonders that Borneo offers, and that can still be experienced. Here, Olesen shares some of his favourites of the more than 350 images in A Visual Celebration of Borneo’s Wildlife and shares the story behind each of them

Published

8 years agoon

By

Guest Writer

All of the authors’ royalties will be donated to Fauna & Flora International for nature conservation work in Southeast Asia.

By Bjorn Olesen

A Visual Celebration of Borneo’s Wildlife makes a powerful case for a relook of the present conservation policies to preserve some of the world’s most stunning biological treasures. With more than 50 percent of the island still forested, there is still potential for long-term protection of these forests if there is a corresponding robust change in the enforcement of laws for forest conservation. Whether this can happen is still uncertain, and is dependent on the collective wills of the national and state governments of Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei. Hopefully, this publication will inspire more people to place a greater value on wildlife and to join the battle to preserve Borneo’s unique nature.

The well-camouflaged Estuarine Crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus) are very territorial and compete aggressively for the best hunting grounds, leaving the sub-adults with the more marginal parts of the river, where food is less abundant. They are classic ambush predators lurking patiently beneath the water while waiting for potential prey. Adults will feed on almost anything which comes to the riverbank, including monkeys, bearded pigs and other hoofed mammals, whereas juveniles will stick to smaller prey like fish, amphibians, small reptiles and mammals.

The beautiful Grey-tailed Racer (Gonyosoma oxycephalum) is common throughout the lowland rainforests of Borneo, where it lives mostly in the forest canopy and understorey. It is renowned for raiding nests for eggs and chicks, and is therefore frequently mobbed by birds when spotted. This striking snake is also often caught for the pet trade, given its attractive colouration.

There are two subspecies of the Critically Endangered Sumatran Rhinoceros: Dicerorhinus sumatrensis sumatrensis of which less than one hundred are estimated to survive in widely separated national parks in Sumatra, and possibly Peninsular Malaysia, and the Bornean subspecies, Dicerorhinus sumatrensis harrissoni. It is the smallest of the world’s rhinoceros with a weight of 500 to 1,000kg (1,100 to 2,200 pounds).

The Sumatran Rhinoceros is a browser, feeding mainly on young tree saplings, leaves and fruits. Most of the foraging occurs in the morning and just before nightfall. Males are usually solitary except during courtship periods, while females are usually found with their single offspring.

Between 1984 and 1996, 40 Sumatran Rhinoceros were captured and translocated from their forest habitat to zoos and rhinoceros sanctuaries all over the world in an effort to start a captive-breeding programme. However, by 2000, all captive-breeding efforts had ended in failure. By this time, the population of captive rhinoceros had been reduced to only three individuals, which were later united at the Cincinnati Zoo, United States, in a last-stand to captive-breed the species.

After many years of failed captive-breeding attempts, Cincinnati Zoo finally had a birth in September 2001, which was the first successful captive birth of a Sumatran Rhinoceros in 112 years. This happy event was followed by two more siblings, also born in the Cincinnati Zoo. Additionally, in the summer of 2012, a calf was born at the Sumatran Rhino Sanctuary in Way Kambas National Park, Sumatra.

The globally threatened Lesser Adjutant (Leptoptilos javanicus) has an impressive wingspan of up to 2.4m (7.8 feet). Its bald head, with a few scattered hair-like feathers and wrinkly grey facial skin, gives it an almost evil-looking appearance. It was previously a common sight in mangrove forests and mudflats, but it has declined, partly because of hunting pressure.

The Black-faced Kingfisher (Lacedo melanops) likes hilly and sub-montane forests. This female briefly raised her crest while holding on to her prey, a Common Flying Lizard (Draco sumatranus) before flying back to the nest. Like other kingfishers, it spends long periods perched on branches looking out for frogs, reptiles and invertebrates on the forest floor. It immobilises its catch by hitting it against a branch before swallowing it head-first.

Borneo Pygmy Elephants (Possible: Elephas maximus borneensis) are herbivores and an adult can eat up to 150kg (330 pounds) of vegetation per day. Their diet consists of more than 150 species of palms, wild bananas, gingers, grasses and trees where they feed on leaves, bark and roots. Elephants also require additional minerals, which they obtain from natural salt licks. On top of that, they consume up to 200 litres (53 US gallons) of water a day.

Unfortunately, one of the reasons why elephants are now so visible in the Kinabatangan Wildlife Sanctuary is because of the fragmentation of their natural habitat, which is severely reduced and isolated by oil palm plantations, roads and human settlements; in other words, they do not have many places to hide. Although we were still fortunate to see newly born calves, the population may not be able to flourish in the long term because of human encroachment and increasing human-elephant conflicts.

The Oriental Pied Hornbill (Anthracoceros albirostris) is the only hornbill in Borneo that does not depend on primary forest habitat for breeding. It is often seen at forest edges and open woodlands where they forage for fruits, but at times also for invertebrates, lizards, snails and small birds.

The Near Threatened Garnet Pitta (Pitta granatina) is absent from Sabah, but can be found in lowland primary and secondary forests in Brunei, Sarawak and Kalimantan. As with other pittas, they rest during the hottest part of the day, remaining very quiet on a perch, which makes them almost impossible to spot during this period.

This male Scarlet-backet Flowerpecker (Dicaeum cruentatum) is feeding one of the chicks with a mistletoe fruit, which is covered with a thick gluey substance; at other times, the chicks are fed with small spiders and other insects. The nest is constructed with plant material. The white cotton-like inner layer comes from the fibers of Kapok fruit (Ceiba pentandra).

To witness a pair of chicks growing up is an eye-opening experience that nobody should miss. Over a couple of days, we were fortunate to observe the comings and goings of a pair of Scarlet-backed Flowerpeckers at their nest in a wild Cinnamon tree (Cinnamomum iners) at eye-level just 2m (6.6 feet) above the ground.

In the same tree there were a number of mistletoes; their fruits form an important part of the diet of flowerpeckers. Mistletoes are parasitic plants, which grow on the branches of a host tree. All the photos were taken with a 600mm lens, with wireless remote control at a safe distance and without flash. During the many hours we spent watching the parents come to this nest, it was noted that more than 50 percent of the time the chicks were fed with the small, sticky fruits of various mistletoe species. In Borneo and throughout the tropics, mistletoes produce berries that are suitably small to be eaten by flowerpeckers. In return, seeds of many mistletoe species are dispersed by the flowerpeckers which pass them out undamaged.

At this point, the seeds are still gluey and will in most cases stick to the bird’s vent feathers. To get rid of the seed, the flowerpecker wipes its bottom on the branch it is perching on. The seed sticks to the surface of the branch, where it slowly develops, sending a sucker into the host tree’s tissue to steal water and nutrients. Like elsewhere in the tropics, flowerpeckers and mistletoes maintain a very close, symbiotic relationship.

Flourishing populations of hornbills like the Rhinoceros Hornbill (Buceros rhinoceros borneoensis), are good indicators of a well-functioning and healthy forest ecosystem. In this shot, you can see a juvenile in a fig tree (Ficus sp.).

The Fig Tree is often prominent and visible in riparian forests not far from the riverbanks. When fruit is abundant, these are some of the best places to locate Orangutans and a host of other mammals and birds. Figs contain natural compounds that have a laxative effect on the animals feeding on them, which ensures that seeds are dispersed over a wider area. As figs can produce fruits throughout the year rather than in synchrony, fruiting figs can be found all year round, thus providing a regular supply of food resources for many fruit-eating animals, including the fig wasps which depend on figs for a large part of the their life cycles.

Hornbills, sometimes called the ‘farmers of the forest’, are vital in dispersing fig seeds, because unlike other animal species, they eat the entire fruit complete with fertile seeds, and then fly long distances before defecating.

The characteristic features of the Proboscis Monkey (Nasalis larvatus) astounded many of the early explorers of Borneo and to this day, visitors remain fascinated with this primate, which is found only in Borneo and confined mainly to mangroves and riverine forests. Although better known as Bekantan in Indonesia, some locals refer to it as Monyet Belanda, or ‘Dutch Monkey’, a sarcastic reference to the Dutch colonisers who were often stereotyped with big bellies and noses.

Wild figs are one of the Bornean Orangutan’s (Pongo pygmaeus) favourite fruits as they are easy to pick and digest. Orangutans are opportunistic foragers, eating more than 400 food items, including fruits, leaves as well as animal protein from insects, reptiles, bird nestlings and eggs. There is also a highly unusual record of a Slow Loris (genus: Nycticebusbeing) having been eaten by an Orangutan.

Fanny Lai is passionate about wildlife. She is a cartoonist, author, travel writer and former Group CEO of Wildlife Reserves Singapore, which comprises Singapore Zoo, Night Safari, Jurong Bird Park and River Safari. She holds an Executive MBA from the University of Chicago Graduate School of Business.

Bjorn Olesen is a retired corporate executive, award-winning wildlife photographer, author and engaged conservationist. A Singapore permanent resident, he lived for 16 years in Malaysia and Indonesia, so Borneo, which he has visited dozens of times, is literally his home turf. His images and articles have appeared in overseas and local publications. All his photos are available free of charge to non-profit NGOs.

Yong Ding Li is pursuing a PhD in conservation biology at the Australian National University. He previously taught science at the National Junior College in Singapore for four years, during which he pursued his interests in biodiversity conservation and birdwatching. Ding Li has travelled widely in the Malay Archipelago, and has published over 25 papers and three books on the wildlife and ecology of the region.

Illustrated with more than 350 images, ‘A Visual Celebration of Borneo’s Wildlife’ is a photographic tribute to the most spectacular wildlife species on the second-largest tropical island on Earth. Drawing from the latest scientific studies, it is filled with captivating little-known facts about the wildlife that modern-day travellers may come across when visiting this enchanting island. It also describes the top 16 wildlife locations in Borneo, with a comprehensive list of recommended reading, websites and blogs provided. You can purchase a copy via this link, with all author royalties being donated to Fauna & Flora International for nature conservation work in Southeast Asia.

All photos (c) Bjorn Olesen. Images feature in Lai, F, Olesen, B & Ding Li, Y 2016: ‘A Visual Celebration of Borneo’s Wildlife’.

You may like

Blakiston’s Fish Owl

Kakapo

A vote to focus attention on Australia’s amazing animals, and their alarming decline

Mexican Grey Wolf

Penguin run undergoes UK sport commentary

Penguin run undergoes UK sport commentary

Seven Worlds, One Planet – Extended BBC Trailer

Thunberg: We will never forgive you

Bilbies Released Back into the Wild in 2018

You must be logged in to post a comment Login