Editorial

Nature Conservation: Making it count

Conservation Photographer Alice Peretie takes a look at the meaning of nature conservation in today’s world, and asks whether there is room for optimism still.

Published

6 years agoon

By

Guest Writer

Almost two years ago, I wrote a short article on sustainable development and conservation, looking at the work Lewa and the NRT (Northern Rangelands Trust) are doing in and for Northern Kenya. I argued that bringing conservation to people was, for me, the obvious solution. Sharing benefits, giving locals the tools to participate, and having a say in practices that are inherently Western. Conservation science is definitely not a Maasai tradition – although, to be fair, conservation-related practices have existed worldwide for thousands of years (Homewood, 2008).

The creation of separate ‘pristine’ nature spaces started in the US with Yellowstone in the 19th century, and was very much imported into Africa during the colonial period – the Serengeti is a good example. Think eviction of locals to create a new Eden, where the colonial man could freely roam, hunt and express his manhood in a ‘naturally wild’ environment – created by himself.

The notion of the wilderness annoys me a bit, in that yes, large, wide, dense, landscapes have that virgin aspect about them, almost waiting to be conquered by a brave soul. And yet the wilderness is one of the reasons why the nature in our cities is not viewed as natural. So we allow ourselves to live in polluted, grey environments, occasionally going to the countryside for a nature break – for those who can, that is.

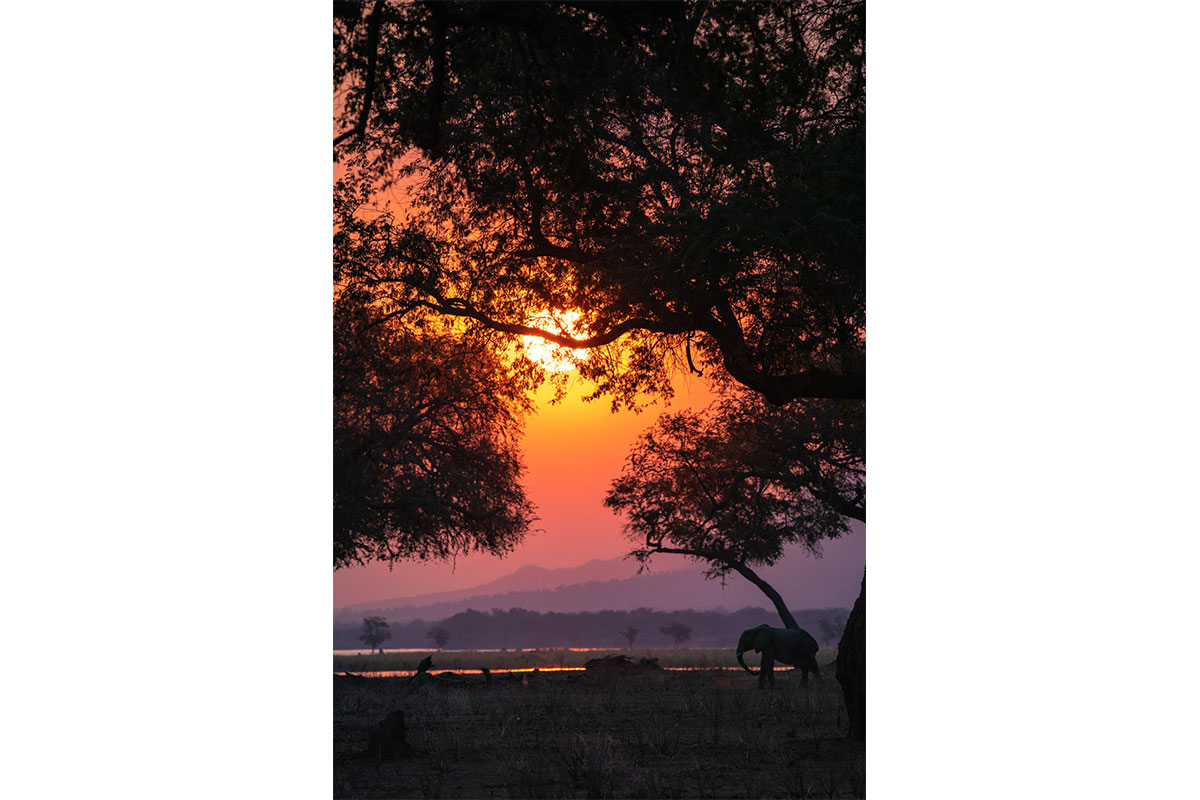

Nature’s beauty: An elephant in the evening glow. Image: Alice Peretie. All Rights Reserved.

So what is conservation?

The key idea I wanted to convey here was to show how far conservation can be from the elitist reputation it has accumulated over the years. With this new paradigm: why could we consider integrating a new set of values in our ways of being.

There is a long-standing debate at the heart of conservation science as to whether we should act based on the environment’s instrumental value (i.e. the economic / utilitarian aspects we can gain from it) or doing it for its intrinsic value – protecting nature for the sake of it.

Personally, I disagree with both. Actually, I disagree with the debate itself.

On the one side, putting an economic value on everything has its positive and negatives, and in most instances, nature never really wins against economic development… But why do we keep opposing both? Nature can cope very well on its own, however not in the form we may appreciate or want. On the other side, it is impossible to justify to a family with ten children living under a dollar a day that, no, they cannot farm that super fertile land opposite their hut because it is an international Protected Area and that nature has a right to exist too.

I think that it is possible to do both, or at least to start with baby steps.

Predators like cheetahs are a critical part of a healthy ecosystem. Image: Alice Peretie. All Rights Reserved.

For me, bringing conservation to people is more about building relationships between man and nature, reconciling the shift created by centuries of portraying our environment as a passive (or sometimes powerful) force in Western societies, waiting for us to dominate it.

Getting to the roots

The roots of conservation as we understand it (i.e. the active management of land and wildlife, different from preservation where we seek to preserve and ecosystem, usually letting it be by fencing it off and protecting it) go far back, centuries ago across civilisations, but around the 19th century it adopted a more regulated, politicised form with individuals like John Muir actively defending the right to spiritualism obtained by immersing oneself in nature.

According to most conservation anthropologists, that period also marked how the British colonial Empire sought to create wild, natural places where they could hunt and enjoy the aesthetic quality East Africa had to offer. The “Maasailand” became fenced off with the creation of the Serengeti National Park, Maasai tribes were evicted and violent events occurred in the name of “Nature protection”.

The official reason was that the lands were over grazed, and cattle damaged them, putting too much pressure and affecting the wildlife (practices that had existed for centuries). The other reason was to rid these spaces of human presence, allowing the colonial expatriates to explore what they viewed as an ‘untouched’ wilderness.

Wild dogs are being rebranded as Painted Wolves. Image: Alice Peretie. All Rights Reserved.

This science was very much contested, an exclusionary ‘Nature for Nature’ approach, excluding local populations from the resources they either exploited or could have exploited, driving conflicts and heightening illicit activities (charcoal trade in Virunga for example, illegal bushmeat trade and poaching, amongst other things). Although there is no single explanation for either of these factors, exclusionary practices were widely – and are still – tied to retaliatory action contributing to loss of diversity.

Conservation has reinvented itself, evolving from ‘Nature for Nature’, to ‘Nature for People’ (itself contested amongst the scientific community this time, for being too focused on human / instrumentalist needs) and finally entering a ‘Nature and People’ paradigm.

So does a new paradigm in conservation imply a new set of values?

Settings the ethical bounds

It makes sense that as a species, humans in this case, will seek to fulfil their needs, both the basic ones (to survive) and the more fulfilling ones that give us a sense of durable satisfaction. This encompasses anything that we care about, that gives us happiness. So, either way, whatever we do for nature protection is, in a way, instrumental – it becomes our personal interest one way or another. Regardless of whether we believe in acting for nature ‘for itself’, I truly believe that progress can be achieved as we move past this debate, no longer criticising or focusing actions for intrinsic (accused of not taking human wellbeing into account as much as it could) and instrumental reasons. A third set of values, elaborated by Chan et al. in 2016, are dubbed ‘relational values’, whereby the bridge between nature and culture is filled, and relational ties are built between both concepts. If we talk about socio-ecologies, we immediately integrate both the ecological and socio-economic spheres in our discourse.

Relational values involve a human collective, where a sense of place is important to people (depicting cultural identity) as a way to connect individuals together (social cohesion), as well as caring for an ecosystem (of which we are a part), and they are primarily individual: you care for the land or for whatever aspect of your environment because it means something to you. With relational values, the purpose is to focus on building relationships (or re-building) between people and nature, as well as relationships between people but including nature.

Protector. Image: Alice Peretie. All Rights Reserved.

When money from conservation funds schools, enables land tenure security for communities, helps raise the health standards (and access to decent care), develops infrastructure, whilst simultaneously raising awareness amongst livelihoods to protect and value their surroundings, not just for cultural or aesthetic but also socio-economic wellbeing purposes, and that the message is transmitted to younger generations, it corresponds to the reinforcement of societies with their surroundings.

Identifying a problem and finding a solution – at any level?

I do not consider myself to be a huge fan of pessimistic, ‘world will end’ stories. Simply because it may have an opposite effect to that desired, in that in desperation, we think, ‘what’s the point?’.

I had the pleasure of having Dr Richard Pearson as a teacher in a conservation biology module during my final year at university. As a prominent researcher in climate change impacts on conservation, he properly advocates against such pessimistic narratives – his fantastic book ‘Driven to Extinction’ offers not only great examples of how ecosystems function on different levels, but equally how synergies of threats (climate change, pollution, habitat loss and fragmentation, etc) are much more important than isolated threats. Yet he still concludes with success stories and outlining the resilience of our natural environment.

Glass half full in a drowning planet

Success stories exist, and we are quick to cast them aside in the name of apocalyptic scenarios. Our planet is far more resilient than we think, however it is the way it adapts to human impact that we may refuse to accept. Harsher environments, current species loss and extinctions, more freak events occurring around the equator, less rainfall as we go towards the poles…Not nice. Yet we have technology, we have research and we have motivation. Researching, adapting our lifestyle and implementing change is actually very relevant. I tend to think that people admonishing radical action are taken less seriously – it is a bit like people who go on a fitness journey: too many restrictions and it is back to square one. There are more than enough articles, publications, blogs out there providing easy advice on how to reduce our global impacts. Typing ‘zero waste advice’ in any search bar will generate a lot of thought-provoking results, as would ‘reduce environmental impact’ searches.

I would add that reading Nobel prize author Albert Camus and researching his conception of the Absurd, the Rebellion and the Passion are a great way to understand how wellbeing, nature and society are intertwined. Reconnect with your environment, reconnect with your Self and look at what you value.

Close up: African painted wolf pups paying close attention. Image: Alice Peretie. All Rights Reserved.

So what next?

As this article comes to an end, I think the main takeaway would be this: what does conserving animals that can have a destructive impact mean (elephants, lions, cheetahs…)? Why should we protect them if they kill livestock, or have led to local displacements, inequality and conflict? Why do we only view broad spaces as natural and view dumpsites and cities as less natural or in an irremediable state?

Conservation is not elitist, it has become necessary in the face of synergistic threats, and yet it does not always have a good reputation.

It enables the balance of ecosystems – of which we are a part. If done properly (i.e. by integrating local opinions and interests in the protection of the whole ecosystem) an equilibrium can be achieved. One that leads to sustainable development, health, education, infrastructure provision and employment.

Conservation should be happening everywhere in the world, cities included – it is not something relevant only to Southern countries or countryside landscapes. The ‘Green city’ concept is a fantastic way to facilitate the integration of relational values: ‘living’ hybrid apartment blocks and houses incorporating live trees and plants illustrate the physical, aesthetic and emotional dependency tied to a sense of place – a sense of home.

It is about building relationships with our environment and finding a balance. For too long, it has been seen as a way to protect ‘pristine’ areas, evicting humans to create a ‘wild’ environment. But we are everywhere, and basic needs will always make people prioritise themselves over the environment.

So why not show and develop how they are linked?

The Leonardo Conservation project, for example, led by big cat specialist NGO Panthera is a great example of how livelihoods are included and benefitting from the conservation of one of their greatest natural enemies. By conserving lions and operating in 15 of 27 lion range countries in Africa, Panthera supports the creation of jobs within communities to help monitor and co-develop mitigation techniques tailored to local parameters.

Intensive research and auditing revealed rewarding communities based on lion densities worked well to encourage local action. This is just one case study – worldwide, projects like these are emerging to get locals involved in both the research, the protection and as receptors of conservation funding.

From there, slowly, we can get people thinking about the intertwined connections between nature and culture.

To support Alice’s Conservation Photography efforts, visit her website at AlicePeretie.com.

References:

Chan, K., Balvanera, P., Benessaiah, K., Chapman, M., Díaz, S., Gómez-Baggethun, E., Gould, R., Hannahs, N., Jax, K., Klain, S., Luck, G., Martín-López, B., Muraca, B., Norton, B., Ott, K., Pascual, U., Satterfield, T., Tadaki, M., Taggart, J. and Turner, N. (2016). Opinion: Why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(6), pp.1462-1465. Accessible at https://www.pnas.org/content/113/6/1462.full

Cronon, W. (1996). The Trouble with Wilderness: Or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature. Environmental History, 1(1), p.7.

Homewood, K. (2008). Ecology of African pastoralist societies. Oxford: James Currey.

Mace, G. (2014). Whose conservation?. Science, [online] 345(6204), pp.1558-1560. Available at: http://science.sciencemag.org/content/345/6204/1558.full.

Neumann, R. (1995). Ways of Seeing Africa: Colonial Recasting of African Society and Landscape in Serengeti National Park. Ecumene, 2(2), pp.149-169.

Panthera.org. (2019). Project Leonardo | Panthera. [online] Available at: https://www.panthera.org/initiative/project-leonardo [Accessed 24 Jan. 2019].

Pearson, R. (2011). Driven to Extinction: The Impact of Climate Change on Biodiversity. Sterling.

You may like

-

Crowdfunding the biggest nature reserve in southern Scotland

-

Mammal Photographer of the Year Winners 2020 Announced

-

The Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Ugly Animals – Conjour Book Review

-

Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2019 – The Winners

-

Comedy Wildlife Photography Awards 2019 – Finalists Announced

-

Race for Survival: The Cheetah

Blakiston’s Fish Owl

Kakapo

A vote to focus attention on Australia’s amazing animals, and their alarming decline

Mexican Grey Wolf

Penguin run undergoes UK sport commentary

Penguin run undergoes UK sport commentary

Seven Worlds, One Planet – Extended BBC Trailer

Thunberg: We will never forgive you

Bilbies Released Back into the Wild in 2018